|

| The Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart, Germany. CreditClara Tuma for The New York Times |

When I stepped off the S-Bahn at the Neckarpark station in Stuttgart on my way to the Mercedes-Benz Museum, I ran into a group of high school students who nicely summed up the two automotive museums they had just visited.

“Mercedes has more details and has more history,” one of them told me. Porsche, he said, was more about Porsche and its racing heritage.

There you have it. My work is done.

Stuttgart is home to these two luxury brands, and as a car guy and automotive journalist, I have always wanted to make the pilgrimage there. Germany does not have the sort of geographic center for its auto industry that the United States has in Detroit. But since the companies’ founders got their 19th century starts in Stuttgart, it comes closest.

My first stop was Mercedes, which presents a captivating walk through the birth of the automobile with the kind of historical sheet-metal eye candy that will wow an automotive fanatic. It’s a tale the company is allowed to own because a founder, Karl Benz, is credited with making the first car, and its other founder, Gottlieb Daimler, was not far behind.

Though Henry Ford made the expensive automobile popular with his affordable Model T in the early 20th century, it was Mr. Benz, an engineer and inventor, who got things started in 1885, when he installed the almost-one-horsepower internal combustion engine he invented into a three-wheel buggy.

The building provides a floor-by-floor circular walk through Mercedes history over its nine floors and 177,000 square feet of exhibition space, with the timeline starting on the top floor. There I found a reproduction of that first car, with the real Daimler car next to it. Actually, a horse, thankfully another reproduction, greeted me as I began my tour at the start of the automobile age, when one horsepower meant what it advertised.

Within a few years cars started to look like cars instead of horse-drawn carriages — for example the museum’s 1902 40 HP, the oldest-existing Mercedes-branded car. Still, the industry used carriage types to describe its models, like phaeton (a light, open carriage), shooting brake (a carriage meant for gamekeepers and sportsmen) and cabriolet (a light carriage with a foldable hood drawn by one horse). Even dashboard is a leftover carriage term — it was the board that insulated the driver from rocks and dirt from the road.

The walls of the ramps that connect the floors are also part of the show. As I made my way down to the fourth floor, which highlighted safety, I learned that the ramp walls were made of polyamide, an airbag material. Clever.

Frankly, the museum can seem overwhelming because there is so much of that history to take in and so many beautiful cars to sigh over, like the 1955 300SL Coupe, known as the Gullwing. You will learn that Mercedes was the name of an important customer’s daughter, Mercédès Jellinek and that the company’s logo, the three-pointed star, symbolizes earth, water and air.

I traveled to the museum by train, but left with a strong urge to drive, but alas, there was no opportunity. I went to the dealership on the bottom floor, but was told test drives must be scheduled about a week in advance.

There is no such problem at the Porsche Museum, about seven miles away from Mercedes. Representatives in the lobby will let you drive an hour and up to about 60 miles, but be aware you have to leave a $3,000 deposit.

No matter — see the museum first. It’s more straightforward than Mercedes’s, with everything on one floor and a loft. It contains more than 60,000 square feet of exhibition space, and the displays are spread out. You can follow the development of Porsche’s models, from the design ultimately used for the Volkswagen Beetle, first created by Ferdinand Porsche, the company founder, to the car that defines the company, the 911. You can see how the sleek Type 64 racecar from the late 1930s led to the beloved Porsche 356 and then to the 911.

And for fun, there’s an area where you can press buttons to hear the engines of several cars, like the Panamera GTS and 911 GT3. Also impressive is the case that displays dozens of trophies from the company’s 30,000 motorsport wins. If you love the brand, especially its racing history, you’ll love this museum.

“Racecars have real road grime, dirt and dents,” Achim Stejskal, director of the Porsche Museum and Historical Communications, wrote in an email about some of the museum’s exhibits. “And all the cars actually run and participate in hundreds of events worldwide every year.”

Both museums touch on World War II and the roles that Mercedes and Ferdinand Porsche played, with Mercedes devoting part of a ramp wall explaining its use of forced labor and the allied bombing of its plants. Porsche has a brief mention of Mr. Porsche’s work as an engineer during the war, when he assisted Germany with tank design.

But do not, under any circumstance, miss the two-hour factory tour across the street from the Porsche Museum. My tour group was full of Porsche owners who were being schooled on why their cars cost so much.

Fun factory facts: It makes about 240 cars a day; 15 percent of the work force is women; it takes 4.5 hours to make the famed boxer engine; and, the tour guide said, most of the leather comes from Austria.

Many of the cars being built that day were headed to China and the United States. I watched as a powertrain arrived on an orange cart under a 718 Boxster for what my tour guide called its marriage into the chassis. A worker hit a button, and the powertrain rose precisely into the chassis. It was a beautiful thing to see.

I would have liked to have followed that car to its new owners, telling them I saw their baby being born.

|

| The first car that bears the name Porsche, originally designed for a long-distance race from Berlin to Rome. CreditClara Tuma for The New York Times |

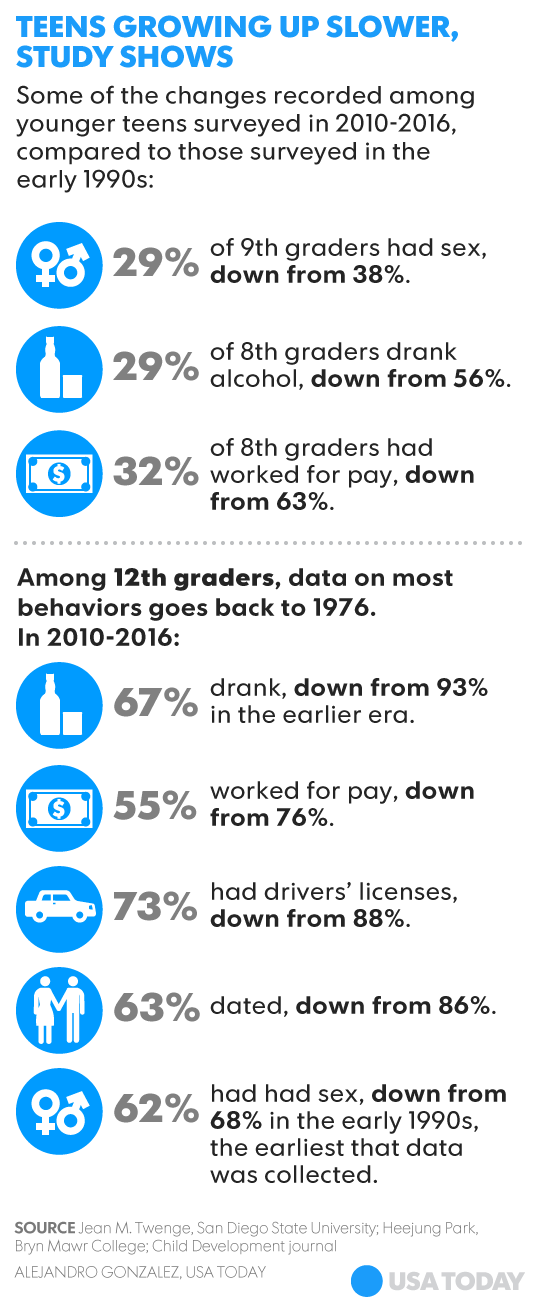

Compared to teens from the 70s, 80s and 90s, today’s teens “are taking longer to engage in both the pleasures and the responsibilities of adulthood,” said Jean Twenge, professor of psychology at San Diego State University and the lead author on a study based on 40 years of survey data published Tuesday in the journal Child Development.

Compared to teens from the 70s, 80s and 90s, today’s teens “are taking longer to engage in both the pleasures and the responsibilities of adulthood,” said Jean Twenge, professor of psychology at San Diego State University and the lead author on a study based on 40 years of survey data published Tuesday in the journal Child Development. The lure of the internet – which might keep kids glued to screens instead of out driving and dating – probably has had some recent impact, Twenge said. And more attentive parenting, sometimes derided as “helicopter parenting,” certainly has played a role, she said.

The lure of the internet – which might keep kids glued to screens instead of out driving and dating – probably has had some recent impact, Twenge said. And more attentive parenting, sometimes derided as “helicopter parenting,” certainly has played a role, she said.

Y