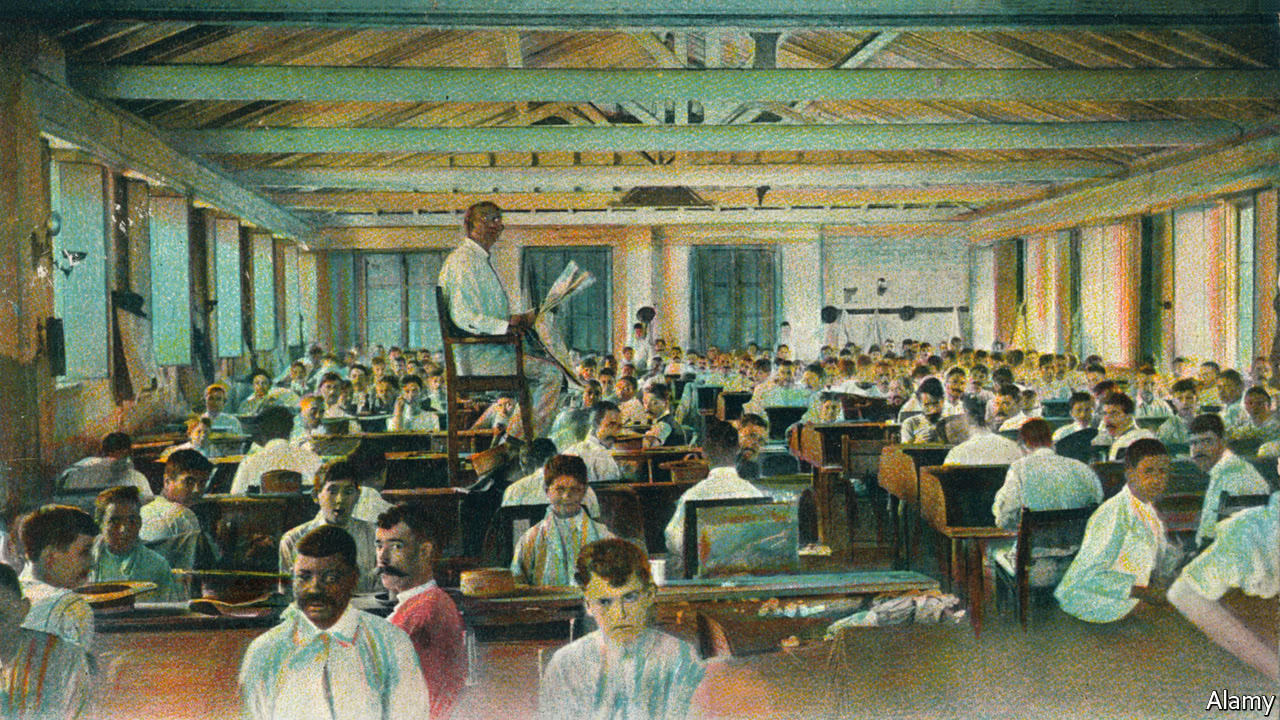

EVERY morning at 8:30 Gricel Valdés-Lombillo mounts a platform at the H. Upmann cigar factory and starts the first of her 30-minute shifts reading to an audience of 150 torcedores, or cigar rollers. Throughout the day she will divert them with snippets of news, horoscopes, recipes and, most important, dramatic readings of literature. In a career that began in 1992 she has read “The Count of Monte Cristo”, a longstanding favourite among torcedores, three times. The popularity of this tale of revenge is the origin of Cuba’s Montecristo brand. Another 250 workers—despalilladoras(leaf strippers), rezagadores (wrapper selectors) and escojedores (colour graders)—hear Ms Valdés-Lombillo’s readings through the public-address system.

Lectores have been reading at cigar factories since 1865, when Nicolás Azcárate, a leader of a movement for political reform, proposed the practice as a way to educate workers and relieve tedium. Perhaps influenced by the texts they heard, cigar workers helped win Cuba’s independence from Spain and later founded trade unions.

When the readings get steamy, torcedores provide an accompaniment of suggestive sound effects. They laugh when a horoscope suggests that someone might inherit a fortune.

Like many lectores Ms Valdés-Lombillo has moved beyond her official role to become a counsellor, confidante and community leader. She has been an announcer at factory baseball games and a eulogist at funerals. If the cafeteria food is too salty or the tobacco leaves become too damp to roll, she will tell the managers.

But lectores no longer act as spurs to dissent. Granma, the Communist Party’s newspaper, is part of Ms Valdés-Lombillo’s daily literary fare. She describes the thoughts and deeds of Raúl Castro, Cuba’s president, and will do the same for his successor. The opinions of exiles and dissidents will not get a hearing. Unlike the cigar workers and the lectores, the party seldom turns over a new leaf.