You can also listen to the audio file by clicking on the Play Button

3/31/2019

Argentina, Japan and Macroeconomics

Why is inflation so stubbornly high in

Argentina and low in Japan? In Argentina, consumer prices were 50% higher in

February than a year earlier, the fastest increase since 1991. In Japan over

the same period, inflation was less than 0.2%, equalling the lowest rate since

2016.

The inertia

in both countries is puzzling. Inflation has stayed low in Japan despite a tight labour market (unemployment has remained at 2.5% or below for over a

year) and high in Argentina despite a fast-shrinking economy: its GDP contracted

by more than 6% year-on-year in the fourth quarter of 2018.

The two

countries, of course, have long perplexed economists. In 1950 Argentina’s GDP per

person was three times that of Japan, according to the Maddison Project

database. The Eva Perón charitable foundation, run by the president’s wife,

shipped 100 tonnes of relief supplies to the war-battered Japanese. Thousands

of Japanese migrated in the opposite direction, creating a population of 23,000

Nipo-Argentinos by the end of the 1960s.

But Japan’s GDP per

person eclipsed Argentina’s around 1970 and is now about twice as high,

measured at purchasing-power parity. Its success and Argentina’s failure defied

predictions. Simon Kuznets, who won the Nobel prize in economics in 1971 for

his work on growth, put it best: there are four types of countries in the

world—developed, undeveloped, Japan and Argentina.

Policymakers

in both countries have tried hard to make them macroeconomically “normal”.

After Shinzo Abe became Japan’s prime minister in 2012, the central bank

promised to raise inflation to 2% in about two years by expanding its asset

purchases. And after Mauricio Macri won Argentina’s presidency at the end of

2015, the central bank promised to raise interest rates enough to bring

inflation down below 17% in 2017 and 12% in 2018.

In both

cases, these new policy frameworks seemed to offer a break with the past. However, both governments have been forced to revisit their

targets and their instruments for achieving them. When price pressures proved

more stubborn than Argentina expected in 2017, the government relaxed its inflation targets to bring them closer in line with reality. But

that led investors to lose faith in the authorities’ resolve to tackle

rising prices. In Japan, many commentators think the central bank should lower

its seemingly unreachable 2% inflation target to something more achievable.

In both countries, workers demand that their pay keeps pace with

the price pressures they feel, not the inflation the central bank promises.

During the spring shunto (or wage offensive), Japan’s big companies

and unions discuss wage deals that set a benchmark for other parts of the

economy. Companies like Panasonic, Hitachi and Toshiba have this year offered

increases in base pay of only 0.3%.

Argentina

has a similar set of negotiations known as paritarias. Some

economists expect them to yield wage increases of 30-35% this year, which will

help keep inflation uncomfortably high. In parts of Argentina the school year,

which begins in March, was delayed by striking teachers demanding salary

increases to offset last year’s inflation and this year’s, whatever it turns

out to be.

Argentina’s

inflationary tendencies reflect its long struggle to live within its means. Argentina has

recorded a deficit in its current account in 30 of

the past 40 years. Japan, on the other hand, has run a surplus since 1981 and

is now the world’s biggest net international creditor.

Despite some signs of

change, Japan’s corporations still hoard cash and other financial assets,

rather than splashing out on the higher wages or dividends a rich economy can

afford.

There are

four types of countries in the world: developed, undeveloped—and economies in

each of those two categories who think they are in the other.

From The Economist (Edited)

3/25/2019

The decline of first-class air travel

|

| Emirates First-Class |

The

rows of hundreds of empty armchairs suggest that something is not quite right.

Airlines are falling out of love with first class. And that is true even of

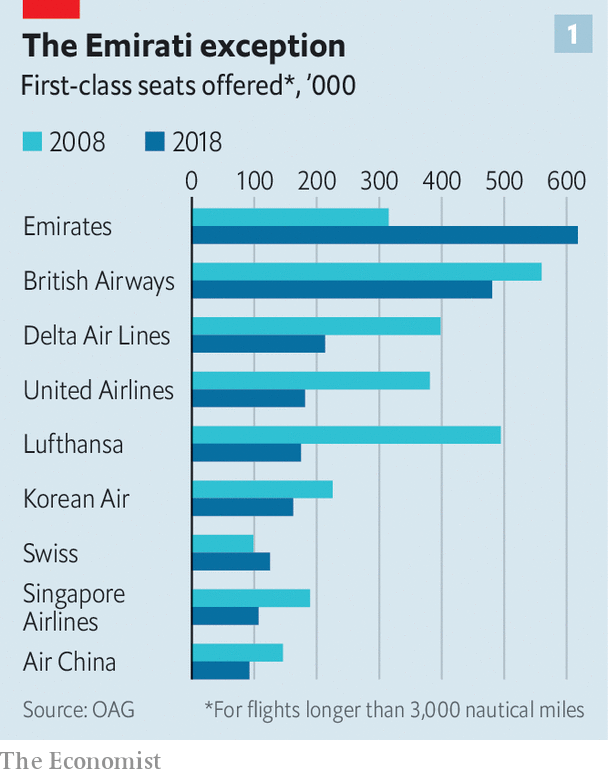

Emirates, which sells far more first-class tickets than any other carrier (see chart 1).

The

rows of hundreds of empty armchairs suggest that something is not quite right.

Airlines are falling out of love with first class. And that is true even of

Emirates, which sells far more first-class tickets than any other carrier (see chart 1).The decline of first-class air travel seems at first glance surprising. Facilities onboard have never been so good. On its a380 superjumbos, Emirates first class provides in-flight showers. Moreover, the number of very rich people has risen sharply. Forbes, a magazine, estimates that the stock of billionaires has doubled to more than 2,100 over the past two decades. And the rest of the luxury-travel business is booming. Richard Clarke of Bernstein, a research firm, estimates that the number of luxury hotels in Asia could increase by as much as 168% over the next decade.

Even so, many analysts predict that first class will soon disappear. In America it is already almost extinct. Ten or so years ago almost all the many hundreds of long-haul aircraft based there offered first-class seating; now only about 20 do. Elsewhere on the majority of the most-travelled long-haul routes the number of first-class seats available has fallen sharply in the past decade (see chart 2).

When commercial aviation got going after the second world war there was only one class: first. Economy appeared in the 1950s. It was followed in the 1970s by business class and in the 1990s by premium economy, to fill the gap between business and cattle class.

Despite the proliferation

of cheaper seats, airlines still make a lot of their money from the more

expensive ones. High demand for flat beds on transatlantic flights is what has

saved European flag-carriers such as British Airways, Air France and Lufthansa

from going out of business.

On short-haul

flights, the low-cost model has won. Most “first-class” passengers on these

routes now sit in seats with the same legroom as economy passengers, albeit

with an empty middle seat.

On short-haul

flights, the low-cost model has won. Most “first-class” passengers on these

routes now sit in seats with the same legroom as economy passengers, albeit

with an empty middle seat.

On longer

routes, new seats that turned into fully flat beds were a game-changer. These

were originally introduced by British Airways in first class in 1995, and much

sought after. If travellers could sleep comfortably in the sky, they could save the

cost of a hotel or, more importantly, a day’s working time. Some years later, in 2000 British

Airways launched a similar seat in business, and most carriers have

followed suit. That has weakened the case for flying first class. Most

companies think a flat bed in business class is good enough for their

employees.

Airlines that

offer first class say they still do so for two main reasons. The first is to

use upgrades from business class as an incentive for loyalty from both

corporate and individual customers. But as the gap between business and first

has narrowed, frequent flyers have begun to respond better to other incentives,

such as access to lounges or to special hotlines.

The second

reason for maintaining first class is also weakening because of the “halo

effect” an airline creates by advertising first-class facilities. Flyers begin to think economy on Emirates,

say, is fancier than on other airlines by association with features in its

first class, such as in-flight showers. This can be an effective marketing

tool. For instance, Etihad, a rival to Emirates in the Gulf, has probably had

more press coverage for its onboard first-class apartments called “The

Residence”, of which it has only ten, than all its 30,000 other seats combined.

Why do some

passengers still want to fly first rather than business? Privacy is one reason.

Smaller cabins and walled-off seats make it easier for a celebrity to fly

unnoticed. Another is flexibility.

First-class passengers want to sleep and eat when they choose, not on a

timetable set by cabin crew, as often happens in business class.

Additionally, first-

and business-class sales are threatened by private jets. These let executives

avoid the wait for a scheduled flight. It is also much quicker to pass through

security in a private-jet terminal than an airport. Moreover, executive jets

are becoming cheaper in relative terms. New shared-ownership and ride-hailing

services allow the cost of a private jet to be spread over many users.

Emirates lounge

manager in Dubai sounds perplexed: “You need to do something different to make

first class worth it.”

3/17/2019

3/16/2019

San Pellegrino's logo

Over the last decade, psychologists at the Crossmodal Research Laboratory at Oxford University, led by Professor Charles Spence, have been investigating the relationship between visual stimuli and taste. In a typical study, researchers created a range of fictitious new drinks-brand designs, where elements such as shape and colour were systematically varied. They asked volunteers to classify the designs in terms of the attributes they expected each drink to have – whether, for instance, they imagined one might be sweet or sour, fizzy or still.

Preliminary research identified what designs the participants associated with particular tastes. Then people were asked to sample an unfamiliar mix of sweet, sour, fizzy and still fruit juices from different types of packaging, to find out whether the expectations set by the bottle influenced how they experienced an unfamiliar product. The researchers concluded that people tend to associate angular shapes with carbonated and bitter-tasting food and drink, and assume that rounder shapes will carry still water or sweet drinks.

These associations seem like a form of synaesthesia, where the senses are crossed in surprising ways. When Duke Ellington heard Johnny Hodges, a saxophonist, play a G, he experienced the sound as a “light blue satin”. But whereas synaesthetic associations differ from person to person, the links between shapes and tastes seem consistent. That’s where San Pellegrino may be on to a winner. The researchers at Oxford found that incorporating a star into a design helps connote the arousing experience of drinking carbonated water. If, on the other hand, you’re flogging a sweet drink, rounded shapes are better: think of the red circle in the 7Up logo or the flowing typeface of Coca-Cola.

Most consumers don’t realise that packaging can have such an effect on them. But next time you go to the drinks aisle at the supermarket, open your eyes and you’ll see stars.

3/09/2019

US Women National Soccer Team vs. USSF

All 28 members of the

World Cup champion U.S. women’s national soccer team are taking legal action

against the USSF (United States Soccer Federation). They claim the organization pays

them less than male players and denies them equal training, travel and playing conditions.

The women filed their lawsuit in

Los Angeles on Friday.

U.S. Women’s

National Team Players Association is not part of the lawsuit. However, its

representatives said in a statement that the association “supports the World

Cup Champion US team.”

Alex Morgan, a member of the women’s team,

said, “Each of us is extremely proud to wear the United State jersey, and we take

seriously the responsibility that comes with that. We believe that fighting for

gender equality in sports is a part of that responsibility.”

The U.S. Soccer Federation did not

immediately comment on Friday.

The U.S. women’s soccer team has seen

great international successes, including three World Cup championships and four

Olympic gold medals.

They will soon defend their title at

the Women’s World Cup in France in June-July.

From VOA News (edited)

3/05/2019

Trump’s former lawyer’s testimony

For ten years, Michael

Cohen was Donald Trump’s attack dog. By his own estimate, the president’s

former fixer threatened more than 500 people or entities at Mr Trump’s request.

But in sworn testimony before the House Oversight Committee on February 27th,

and armed with documents, Mr Cohen called his former boss “a racist…a con man…and

a cheat” who is “fundamentally disloyal” and a threat to American democracy.

Mr Cohen’s

accusations were not entirely new. But hearing them made openly before

Congress, under penalty of perjury, crystallised how extraordinary they are. Mr

Cohen said that Mr Trump knew in advance that WikiLeaks would release stolen

emails damaging to Hillary Clinton’s campaign. That would make the campaign

complicit in an attack by a foreign intelligence service.

Mr Cohen also

entered into evidence a pair of cheques—one signed by Mr Trump from his

personal account and the other from his trust account, each for $35,000, both

from 2017, after he took office—which he said were reimbursements for hush

money paid to a pornographic-film actress. Mr Cohen says that as late as

February 2018, Mr Trump told Mr Cohen to say that he did not know about these

payments.

He also brought

three financial-disclosure statements to illustrate his claim that Mr Trump

inflated his net worth when he wanted people to think he was rich, and deflated

it to minimise his taxes. In 2012-13, according to the statements, his net

worth rose from $4.6bn to $8.7bn—due largely to his “brand value”, which Mr

Trump did not mention in 2012 but by 2013 was somehow worth $4bn. Mr Cohen also

said that Mr Trump inflated the value of his assets to an insurance firm, which

would count as fraud.

Mr Cohen said Mr

Trump, “knew of and directed the Trump Moscow negotiations throughout the

campaign and lied about it.” He said he briefed Mr Trump, as well as Donald

junior and Ivanka, about the project around ten times in 2016. Mr Cohen said he

knew of no “direct evidence that Mr Trump or his campaign colluded with

Russia.” But, he said, “I have my suspicions,” noting Mr Trump’s desire to win

at all costs.

Republicans on

the committee implied that Mr Cohen’s testimony was a plot to land a lucrative

book or film contract. And they highlighted that he was convicted of lying to

Congress, among other things, and will soon begin a three-year prison sentence.

Mr Cohen accused

Trump of conduct more serious than Bill Clinton’s lies about an extramarital

affair. The prospect of impeachment is closer now than it was before Mr Cohen

testified.

From The Economist (edited)

3/04/2019

Lotteries and VAT

People pay taxes because governments say they must and society says they should. But what if tax compliance became fun?

Governments around the world are encouraging consumers to ask for receipts by turning them into lottery tickets. Taiwan was an early experimenter, in 1951. The past decade has seen a flurry of such schemes: China, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Portugal, Romania and Slovakia all now have them. Latvia will launch one later this year.

The aim is to make it harder for retail businesses to evade taxes. Worldwide, 20-35% of government revenue comes from value-added taxes (VAT) or similar levies on consumption.

The problem is not business-to-business transactions. When selling direct to consumers, it is tempting to accept cash without recording the sale. The idea of a receipt-lottery scheme is to give customers an incentive to ask for receipts, thereby forcing sales to be recorded and taxed. Receipts are printed with a code that is then submitted into a central lottery, which awards prizes ranging from money to cars and holidays.

The Brazilian state of São Paulo, for example, grants citizens who give their taxpayer number when making a purchase not just a chance to win a prize, but a rebate of 30% of the sales taxes they have paid.

According to a report for the European Commission in 2017, of the ten European countries with the biggest shortfalls in collection of VAT in 2014-15, nine have, or are setting up, a receipt-lottery scheme. (Italy is the exception.) Though a receipt lottery cannot end evasion on its own, says Jonas Fooken, a researcher at the University of Queensland, adding “a bit of magic” to mundane purchases can help.

Article from The Economist (edited)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)