|

| Emirates First-Class |

The

rows of hundreds of empty armchairs suggest that something is not quite right.

Airlines are falling out of love with first class. And that is true even of

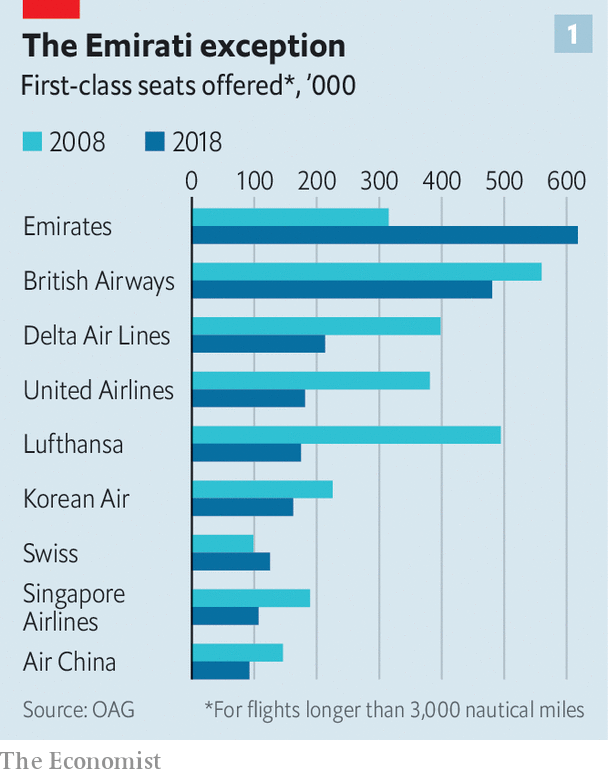

Emirates, which sells far more first-class tickets than any other carrier (see chart 1).

The

rows of hundreds of empty armchairs suggest that something is not quite right.

Airlines are falling out of love with first class. And that is true even of

Emirates, which sells far more first-class tickets than any other carrier (see chart 1).The decline of first-class air travel seems at first glance surprising. Facilities onboard have never been so good. On its a380 superjumbos, Emirates first class provides in-flight showers. Moreover, the number of very rich people has risen sharply. Forbes, a magazine, estimates that the stock of billionaires has doubled to more than 2,100 over the past two decades. And the rest of the luxury-travel business is booming. Richard Clarke of Bernstein, a research firm, estimates that the number of luxury hotels in Asia could increase by as much as 168% over the next decade.

Even so, many analysts predict that first class will soon disappear. In America it is already almost extinct. Ten or so years ago almost all the many hundreds of long-haul aircraft based there offered first-class seating; now only about 20 do. Elsewhere on the majority of the most-travelled long-haul routes the number of first-class seats available has fallen sharply in the past decade (see chart 2).

When commercial aviation got going after the second world war there was only one class: first. Economy appeared in the 1950s. It was followed in the 1970s by business class and in the 1990s by premium economy, to fill the gap between business and cattle class.

Despite the proliferation

of cheaper seats, airlines still make a lot of their money from the more

expensive ones. High demand for flat beds on transatlantic flights is what has

saved European flag-carriers such as British Airways, Air France and Lufthansa

from going out of business.

On short-haul

flights, the low-cost model has won. Most “first-class” passengers on these

routes now sit in seats with the same legroom as economy passengers, albeit

with an empty middle seat.

On short-haul

flights, the low-cost model has won. Most “first-class” passengers on these

routes now sit in seats with the same legroom as economy passengers, albeit

with an empty middle seat.

On longer

routes, new seats that turned into fully flat beds were a game-changer. These

were originally introduced by British Airways in first class in 1995, and much

sought after. If travellers could sleep comfortably in the sky, they could save the

cost of a hotel or, more importantly, a day’s working time. Some years later, in 2000 British

Airways launched a similar seat in business, and most carriers have

followed suit. That has weakened the case for flying first class. Most

companies think a flat bed in business class is good enough for their

employees.

Airlines that

offer first class say they still do so for two main reasons. The first is to

use upgrades from business class as an incentive for loyalty from both

corporate and individual customers. But as the gap between business and first

has narrowed, frequent flyers have begun to respond better to other incentives,

such as access to lounges or to special hotlines.

The second

reason for maintaining first class is also weakening because of the “halo

effect” an airline creates by advertising first-class facilities. Flyers begin to think economy on Emirates,

say, is fancier than on other airlines by association with features in its

first class, such as in-flight showers. This can be an effective marketing

tool. For instance, Etihad, a rival to Emirates in the Gulf, has probably had

more press coverage for its onboard first-class apartments called “The

Residence”, of which it has only ten, than all its 30,000 other seats combined.

Why do some

passengers still want to fly first rather than business? Privacy is one reason.

Smaller cabins and walled-off seats make it easier for a celebrity to fly

unnoticed. Another is flexibility.

First-class passengers want to sleep and eat when they choose, not on a

timetable set by cabin crew, as often happens in business class.

Additionally, first-

and business-class sales are threatened by private jets. These let executives

avoid the wait for a scheduled flight. It is also much quicker to pass through

security in a private-jet terminal than an airport. Moreover, executive jets

are becoming cheaper in relative terms. New shared-ownership and ride-hailing

services allow the cost of a private jet to be spread over many users.

Emirates lounge

manager in Dubai sounds perplexed: “You need to do something different to make

first class worth it.”