Avi Schiffmann climbed into

bed after attending a demonstration in San Diego protesting Russia’s invasion of

Ukraine, but sleep didn’t come.

“I couldn’t stop thinking

about what I could do to help,” said Schiffmann, 19, a Harvard University

student who was visiting San Diego while taking a semester off. “I wanted to do

something with an instant impact.”

Two years earlier, when he

was 17, he developed a website, ncov2019.live, to help track the spread of the coronavirus around the world. The site was so well

received that Schiffmann was presented a Webby

Person of the Year award

online in 2020 by Anthony S. Fauci.

Schiffman suddenly sat up

in bed with an idea: Make a website for Ukrainian refugees who needed places to

stay in other countries. He put

out a tweet.

“A cool idea would be to

set up a website to match Ukrainian refugees to hosts in neighboring

countries,” Schiffmann posted.

He followed up asking for

help from people who spoke other languages to translate the website into

Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, Czech and Romanian.

Then he texted his Harvard

University freshman classmate Marco Burstein, an 18-year-old computer coding

whiz, to ask if he could help him quickly develop a website.

Burstein was 3,000 miles

away in Cambridge, Mass., and had papers to write and classes to attend. Anyway,

he was in.

The pair worked almost

nonstop texting and on FaceTime to create

a website that would be easy to

navigate for people offering help and those seeking it.

On March 3 — three days and

only five hours of sleep later — they launched Ukraine

Take Shelter, a site in 12

languages where Ukrainian refugees fleeing war can immediately find hosts.

“If someone has a couch

available, they can support a refugee,” said Schiffmann. “And if somebody has

an entire house, they can put it on the site and support a whole family.”

“What we’ve done is put out

a super fast version of Airbnb,” he

said.

In the first week, more

than 4,000 potential hosts around the world offered a place to stay through

Ukraine Take Shelter, and the number of hosts grows each day.

In some cases, the hosts

are even buying airline tickets to help families.

“The number of new hosts

we’re getting every day is mind-blowing, and we’re seeing immediate results in

how the website is making a difference,” he said. “It’s literally saving lives

for people in a terrifying situation.”

“We found that existing sites run by governments

to help refugees complicated,” Schiffmann said. “Somebody running away from

explosions and gunfire is under stress and needs something easy to use”.

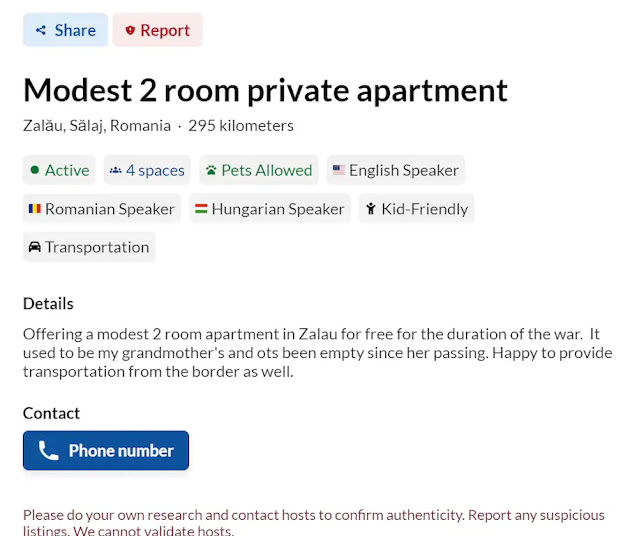

On the Ukraine Take Shelter

website, refugees type in their current locations and dozens of host offers pop

up from the closest towns in neighboring countries. They can also specify the

number of people who need shelter and whether they have pets or family members

with special needs.

Listings offer

accommodations ranging from a sofa in a one-bedroom apartment in Lithuania to a

nine-bedroom chalet with eight bathrooms in Romania.

“I am a medical student, as

is my boyfriend and we live in a one-bedroom apartment in the center of Kaunas,

Lithuania,” wrote a volunteer host who had an available sofa. “We can only

offer our couch in the living room with free food, supplies and anything else

that is necessary. We don’t have any kids and could babysit as well.”

Some hosts don’t have room

for people, but they’re offering assistance for pets.

“We are offering a

temporary place for one dog,” wrote a host from Latvia. “We are living in an

apartment building, but with a lot of green areas and dog parks next to us.

Your dog will have food, care, a bed and long walks!”

The key to the website’s

design is its simplicity, said Schiffmann, noting that exact addresses aren’t

provided for the hosts or the refugees for security reasons.

“Our goal was to get the

site up as fast as possible to help as many people as possible, and that’s

exactly what is happening,” he said.

Both he and Burstein were

drawn to building webpages when they were young and learned how to tackle

coding by watching YouTube videos, said Schiffmann, who grew up in the Seattle

area.

Burstein, who grew up in

Los Angeles, learned to program computers when he was in third grade.

“Avi and I met after we

came to Harvard,” he said. “I made a website last summer so that Harvard

students could see what classes all their friends were taking, and Avi reached

out to me about it.”

The two ended up bonding

over their common interest of using technology to solve problems, said

Burstein.

“We’re incredibly fortunate

to be going to Harvard and to have loving families and live in a safe

environment,” he added. “We felt it was our turn to give back.”

Schiffmann, left, and Marco Burstein at Harvard University

From The Washington Post (edited)

Photos: Courtesy of Avi Schiffmann