In 1991 Mauricio Macri, son of a wealthy industrialist, was kidnapped. His captors held him for two weeks before his family paid a $6m ransom. Mr Macri, Argentina’s president since 2015, says the ordeal persuaded him to abandon business and contribute to society by taking up politics. His second career has proved hardly less traumatic. Argentina’s plunging currency led Mr Macri to confess on September 3rd that “these were the worst five months of my life since my kidnapping.”

Another recession, the second since Mr Macri took office, now seems inevitable. In May the central bank raised interest rates to 40% to tackle a currency crisis that has seen the peso lose more than half its value against the dollar since the start of the year. The next month the government secured a $50bn credit line from the IMF, the largest in the fund’s history. In August, as the peso continued its slump, the central bank raised rates to 60%. None of these measures bought more than temporary relief. Mr Macri has appealed to the IMF to accelerate the loan payments. A new round of negotiations with the fund began on September 4th and have yet to conclude.

With a presidential election due in October 2019, investors fear that the crisis will precipitate Mr Macri’s departure and a return to the disastrous populist policies of his Peronist predecessor, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner Until recently Mr Macri appeared assured of a second term in office as reward for his efforts to repair the economic damage inflicted by Ms Fernández. Soon after taking office, his government slashed export taxes, lifted currency controls and resolved a disagreement with bondholders to restore access to international capital. Spending cuts were implemented gradually to protect the third of Argentines below the poverty line.

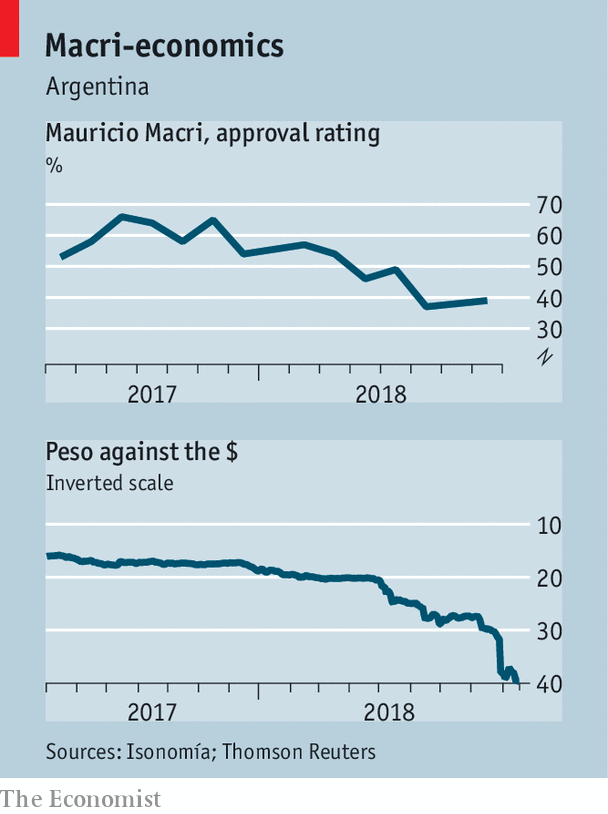

The strategy worked. There was a painful recession in 2016, the result of raising interest rates to tackle 25% inflation, but after that the economy rebounded. In 2017 GDP grew by 2.9%. Mr Macri’s coalition won mid-term congressional elections in October. Yet despite his efforts to defuse it, the fiscal time-bomb bequeathed by Ms Fernández has detonated this year. In April rising yields on US Treasury bonds hit Latin American currencies as investors sold risky assets. Argentina’s fiscal and current-account deficits, along with its pile of foreign-denominated debt, singled it out for punishment. The peso slumped, along with approval of Mr Macri (see chart).

The strategy worked. There was a painful recession in 2016, the result of raising interest rates to tackle 25% inflation, but after that the economy rebounded. In 2017 GDP grew by 2.9%. Mr Macri’s coalition won mid-term congressional elections in October. Yet despite his efforts to defuse it, the fiscal time-bomb bequeathed by Ms Fernández has detonated this year. In April rising yields on US Treasury bonds hit Latin American currencies as investors sold risky assets. Argentina’s fiscal and current-account deficits, along with its pile of foreign-denominated debt, singled it out for punishment. The peso slumped, along with approval of Mr Macri (see chart).

In response, the government announced its latest plan to regain the confidence of investors on September 3rd. It has promised to balance the budget in 2019, a year sooner than agreed on in June with the IMF. It plans to eliminate the primary fiscal deficit, which is forecast to reach 2.6% of GDP this year, by levying a new tax on exports, and reducing subsidies on public transport and electricity. As well as appeasing investors, the measures are aimed at persuading the IMF to disburse credit earmarked for 2020 and 2021. But the fund may seek “modifications in return for more financing,” says Edward Glossop of Capital Economics, a consultancy.

The coming months are unlikely to offer Mr Macri respite. The government expects the economy to shrink by 2.4% this year and inflation to reach 42%. Next year it predicts a further contraction of 0.5% and inflation averaging 23%.

A worsening economy may prompt social unrest. “Much depends on how much patience Argentines are willing to show the government,” says Juan Cruz Díaz of Cefeidas Group, a consultancy.

If Mr Macri’s ratings continue to decline, he could decide to stand down to make room for one of his protégés, perhaps María Eugenia Vidal, the charismatic governor of Buenos Aires province, or Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, the mayor of Buenos Aires. Aides to Mr Macri discount that prospect. But, as Mr Macri knows, his career can change course suddenly.