A tour of the modernist building of the

Harley-Davidson museum in Milwaukee helps to explain why the midwestern maker

of motorcycles has iconic status, but also why it is struggling. Nearly all the

visitors are white, middle-aged men, some in leather and heavily tattooed,

others dressed conservatively. Harley is the quintessential baby-boomer brand but

its customers are slowing down.

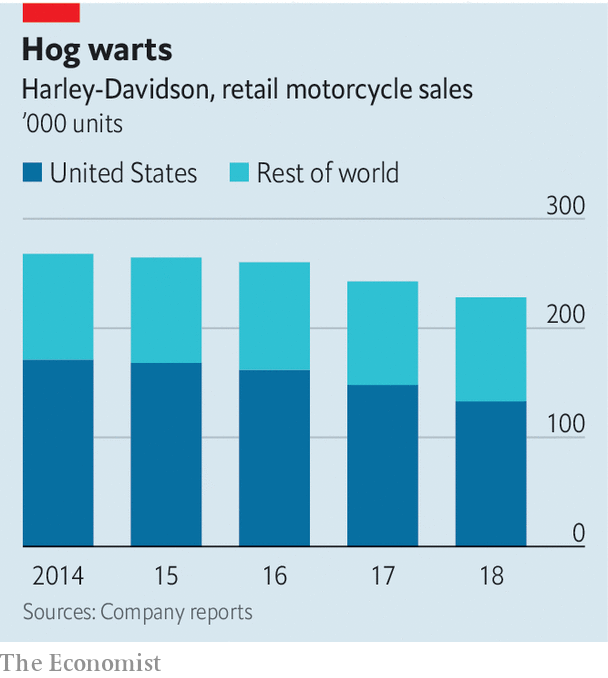

The firm has been losing sales at home for eight

consecutive quarters. The total cost of tariffs (those imposed specifically on

its bikes by the European Union and China, and also those levied by America on

imports of steel and aluminium, its main materials), together with

restructuring costs, wiped out its profits.

The 116-year-old business has been through tough times

before. It almost went bankrupt in 1981 when America was in recession and

Japanese makers of motorcycles dumped unsold inventory onto the American market

at extremely low prices. Then a group of employees bought the company,

persuaded the government to impose tariffs on Japanese bikes, improved the

quality of its wares and returned to the heavy retro look of the 1940s. That

did the trick for baby boomers who bought the expensive toys cleverly marketed

as a symbol of freedom, individualism and adventure on America’s scenic roads.

Tariffs are the enemy again: the company expects their

cost to rise to $120m this year.

Harley’s other challenge is to win over millennials,

women and non-white buyers.

Dealers are counting on the 16 new motorcycle models to

be more affordable, and attractive to a wider audience both in the USA and in

international markets.

Harley may suffer from the quality of its older motorcycles.

Sales of used bikes are outpacing those of new ones by three to one (a decade

ago it was the other way around). But while old bikes, and Harley accessories

and clothing sold in specialist shops and on Amazon are selling well, they

won’t compensate for the damage done by tariffs and youthful disinterest.

From The Economist (edited)